By Muhammad Younas — Khyber District, Pakistan :

The Issue: Trapped by Conflict and Silenced by Poverty

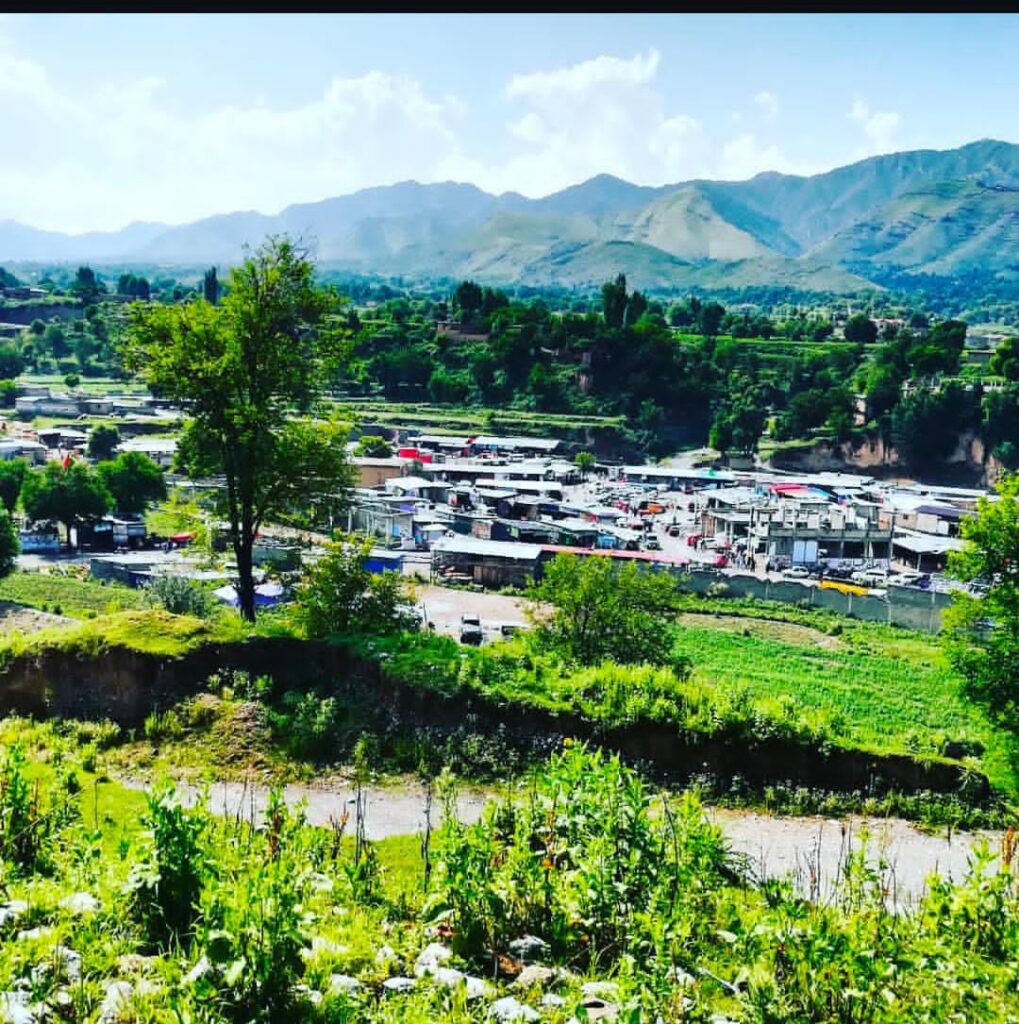

In Pakistan’s Khyber District, the war never truly ends; it merely shifts its form and fades from the headlines. The Tirah Valley, once known for its breathtaking hills and fertile fields, now echoes with the grief of families caught in a conflict they did not start and cannot escape. For decades, this remote region has lived through endless cycles of displacement and return, each wave leaving deeper wounds on a population long forgotten by the state.

Today, thousands are again on the move, not because of floods or famine, but because of renewed fighting between armed groups and security forces. Yet there are no official camps, no formal evacuations, and no registration lists. The displaced are invisible, surviving in borrowed rooms and half-collapsed homes, silenced by fear and poverty.

Among them is Amin Gul, a father of five, whose story has come to symbolize the unbearable cost of another unspoken war.

A Home Shattered by a Single Shell

In the rugged heart of Tirah, forty-five-year-old Amin Gul has lost not only his home but also his wife to the latest wave of violence.

In Bara’s Spin Dhand area, relatives gather at a family guesthouse to offer condolences. Inside a small, borrowed house nearby, nearly forty members of Amin’s extended family are taking refuge, unsure of what comes next.

Amin recalled that a strict curfew had been in place for two days. No one was allowed to leave their homes while heavy gunfire and explosions echoed through the valley. On the afternoon of October 28, as the sound of shelling grew closer, Amin gathered his wife, children, and his brothers’ families—around forty people—and moved them to the lower rooms for safety. He remained upstairs to monitor the situation.

Moments later, a heavy mortar shell struck the very room where the women and children were sheltering.

“When I rushed downstairs,” Amin recounted, his voice tight, “the house was buried in dust. I could hear only screams. I stepped over bodies, not knowing who was alive or dead.”

His twenty-year-old son, Umar Khan, emerged moments later, carrying his mother in his arms. She had already died. Amin’s ten-year-old daughter Afshan, eight-year-old niece Maria, and fifty-year-old sister were all critically injured.

Amid the ongoing shelling, Amin managed to load the wounded and his wife’s body into a pickup truck, racing them to a nearby doctor who confirmed the death. On the return journey, their driver, thirty-year-old Dilshad, was shot and wounded by gunfire from an unknown direction. The vehicle, carrying twenty terrified relatives, was abandoned, forcing them to continue the harrowing journey on foot.

It wasn’t until noon the next day that they were permitted to move the body on foot. Family members carried the coffin across steep, rocky terrain for two hours before reaching waiting vehicles. She was buried in Bara, while the injured children remain under treatment.

Children Haunted by Fear

It is the children who continue to pay the highest price: in fear, in loss, and in silence.

In the dimly lit rooms of Bara, nightmares have become more common than dreams. For Amin Gul’s children, the echo of that single explosion has changed everything.

“They cry whenever I mention going back,” he says quietly, his voice breaking. “They say they can never return to that house—the house where their mother was martyred, where the walls are still stained with her blood.”

His eldest son, Umar, still carries the memory on his skin. When he pulled his mother’s body from the rubble, her blood soaked through his clothes. He initially refused to change them, calling it “my mother’s sacred blood.” It took hours of persuasion before he finally did. Today, the children wake at every loud sound. The simple crack of firewood or the rumble of a passing truck can trigger the terror of that afternoon.

A Valley at War with Itself and the Jirga Divide

The Tirah Valley, home to nearly 300,000 people, was once a place of tourism and fertile crops. Now, its mountains hide ruins and fear. Security officials claim that residents were advised to evacuate again amid fresh operations against armed groups, but locals say they have nowhere else to go.

Syed Muhammad, a resident, recalled that when people returned in 2015 after a major military operation, their homes were in ruins, their lands barren, and their livestock gone. “No government support came,” he said. “We rebuilt our lives ourselves—and now it’s happening all over again.”

With no formal assistance, unofficial figures suggest more than 500 families have already fled, surviving with relatives in drastically overcrowded homes. Men often remain behind to guard their property. When contacted, officials at the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) and district administration offered no comment.

Peace talks between local elders and armed groups have been ongoing for months, but trust is shattered. On November 2, a fragile ceasefire was reached when the Bar Qambarkhel National Council convinced a banned militant group to withdraw from residential areas.

But soon after, elders accused the militants of violating the peace pact—sworn on the Holy Quran—by resuming attacks from civilian zones. The security forces responded with counter-shelling, trapping ordinary families once again in the crossfire.

At an emergency Jirga, tribal elder Haji Zahir Shah Afridi declared that every household of the Bar Qambarkhel tribe would be represented in a Grand Jirga to decide the valley’s future. “We cannot allow militants to use our homes and mosques as shields,” he said. “This time, the people will decide their own peace.”

The Day of Two Jirgas

As news of renewed fighting spread, two very different Jirgas met on the same day—symbolizing the painful divide between local suffering and political symbolism.

In Tirah, hundreds of elders gathered for the Afridi Grand Jirga, rejecting evacuation orders and vowing to stay. “Tirah is our mother,” one elder declared. “We cannot leave her again and again. We have buried our loved ones here.”

Meanwhile, miles away in Peshawar, the FATA Loya Jirga convened to reaffirm its commitment to the merged districts—a gesture many locals dismissed as distant and detached from the gunfire echoing in their mountains.

Together, these two gatherings revealed a painful truth: while the government debates policy, the people of Tirah continue to bleed in silence.

An Economy Fueled by Opium and Fear

At a recent media briefing, DG ISPR Lieutenant General Ahmed Sharif Chaudhry shed light on another dimension of the conflict: the drug economy. He noted that 12,000 acres of poppy are cultivated in Tirah, producing billions in illicit revenue. He claimed that 70 percent of the local population is tied to this trade, which now finances militants, smugglers, and corrupt officials alike.

Tirah has become both a battleground and a marketplace—where survival depends as much on opium as it does on peace.

Chief Minister Sohail Afridi recently announced that peace Jirgas will be held across all tribal districts, culminating in a final conference in Peshawar. Yet for the people of Tirah, promises of peace have begun to sound like echoes: familiar, fading, and unfulfilled.

“I no longer believe in peace talks,” said Amin Gul, his eyes fixed on the mountains. “We’ve heard them for years. But nothing changes. Only the graves increase.”