Muhammad Younas

In Pakistan, disasters no longer strike as rare shocks. They return year after year, reshaping valleys and uprooting lives. Floods submerge villages, landslides tear down mountain slopes, and glacial lakes burst without warning. Each season, the destruction deepens.

Climate change is often held responsible, and rightly so. But there is another story, one rooted in the country’s own soil. Pakistan’s forests — once a shield for its mountains and river valleys — are disappearing. Where trees once absorbed rains and steadied hillsides, there are now scarred landscapes, stripped bare by chainsaws, fires, and unchecked construction.

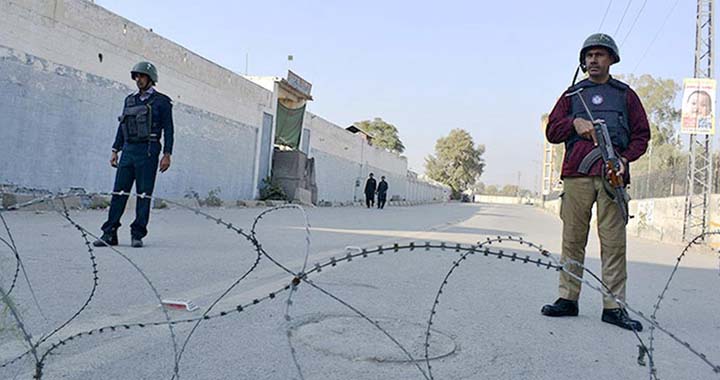

When Conflict Stripped the Land

The loss of forests is an environmental tragedy but also a legacy of war. For nearly two decades, much of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the tribal belt lived through militancy and military operations. Villages emptied, families fled, and whole communities were displaced. In those years of turmoil, forests became a silent casualty.

Timber mafias thrived in the absence of governance. Militants financed themselves by cutting old-growth trees. Military operations cleared valleys, and desperate displaced families often relied on firewood for survival. When the dust of conflict began to settle, the green cover that once shielded these mountains had thinned dramatically.

Development at a Cost

When peace returned, another wave of change began. Roads, highways, and mega development projects spread through the valleys. Motorways now cut across hills that were once thick with pine and oak. New settlements and real estate projects followed, eating into farmland and forest edges.

These projects brought connection, mobility, and commerce — long denied to many communities. But they also brought bulldozers and chainsaws. Hillsides were carved open to lay asphalt. Streams were diverted. Construction fuelled demand for timber. In the name of progress, fragile ecosystems were disrupted.

The Shrinking Green Shield

According to Global Forest Watch, in 2020 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa still had more than 2.3 million acres of natural forest. But by 2024, hundreds of hectares had vanished. Malakand has lost nearly half its tree cover since 2005. Hazara has seen a steady decline. In Chitral, experts warn that one quarter of its forests may vanish by the end of this decade.

Behind every statistic is a human cost. When riverbanks lose their tree cover, floods surge into homes. When hills are stripped bare, landslides bury roads. When watersheds collapse, women and children walk farther each year for clean water.

The Human Toll

In Chitral’s Arandu Gol, villagers describe how recent clearances left their valley exposed to floods. In Hazara, illegal cutting inside Ayubia National Park and the Makhniyal forests has eaten away at one of the last green lungs of the region.

In Babusar and Mansehra, families rebuild homes after every landslide. In Buner and Swat, farmers watch their crops drown in flash floods. Each year, displacement returns in a new form — not from combat, but from disaster.

The lessons are not new. Pakistan lived through devastating floods in 1992 and again in 2010. Both revealed the same truth: without forests, there is no safety. Yet the cycle repeats, only now more ferociously.

A Question of Responsibility

Pakistan has pledged under the Paris Agreement to protect ecosystems and cut emissions. Yet on the ground, forests continue to fall. Logging mafias, real estate developers, and unchecked contractors strip the hills with impunity. Nature is treated as merely a commodity.

Yes, Pakistan suffers unfairly from global warming. International finance is slow, and the burden is heavy. But this cannot excuse neglect at home. We can enforce laws, halt illegal cutting, and restore degraded lands. Ignoring these choices is a decision to embrace catastrophe.

Choosing Survival

Resilience is not built with concrete walls. It is built by restoring ecosystems, replanting, and protecting what still stands. Commercial development without balance is destruction by another name

Forests are more than timber. They are barriers against floods, makers of rain, keepers of carbon, and lifelines for millions. Conflict has scarred them. Development has chipped away at them. To lose what remains is to gamble with the survival of communities already tested by war and disaster. To protect them is to choose life.